The party is over in commercial real estate. Here’s what to expect in 2023.

An era of cheap debt that helped lift prices on hotels, office buildings and other U.S. commercial properties to dizzying new heights has ended.

Higher financing costs already were a concern for 2023, with billions of dollars worth of older commercial mortgages coming due. Adding to the woes, top tech titans, including Meta Platforms

META,

in recent weeks have retreated from splashy office leases.

“You had all these large tech companies signing big new leases, which was getting the market comfortable with the idea that the office sector was going to recover over the longer term,” said Greg Handler, head of mortgage and consumer credit at Western Asset Management.

Now, one of the few brights spots in the near $21 trillion commercial real-estate market has become another headwind, Handler said. “It raises real questions about who is going to pick up that extra square feet, and at what price.”

Property puzzle

Insurance companies and banks often make commercial property loans to hold on their books, while Wall Street packages up the debt into bond deals.

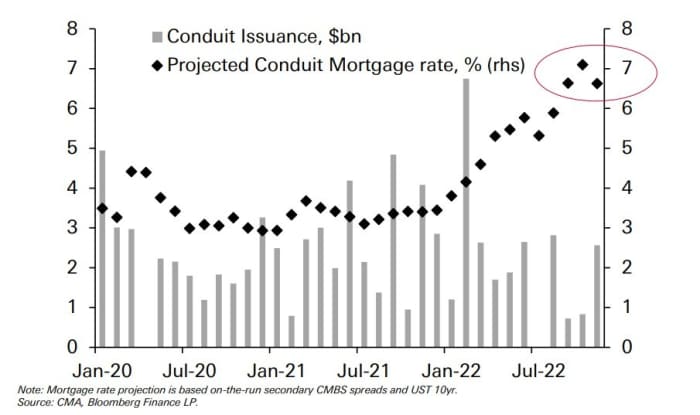

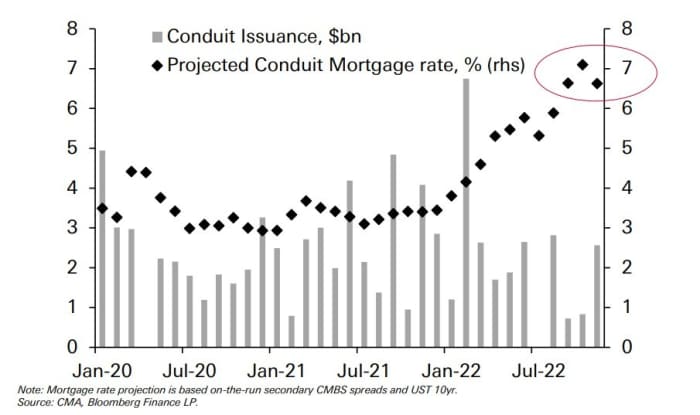

Issuance of bonds, called commercial mortgage-backed securities, or CMBS, has been a driving force in property finance for decades. But this year, “conduit” bond issuance backed by multiple borrowers and properties collapsed as mortgage rates topped 7% (see chart), according to Deutsche Bank research.

Collapse of a key property funding source

CMA, Bloomberg, Deutsche Bank Research

Landlords tend to default when debt comes due and financing dries up, a situation that can be exacerbated when a property’s cash flows or valuation falls.

While public markets this year repriced commercial real estate dramatically lower, private markets have yet to budge much from record levels, despite historic losses in stocks, bonds and other financial assets.

See: Office-property woes are driving REIT carnage as 2022 shapes up to be second-worst year on record

The Dow Jones Equity REIT Index

DJDBK,

was on pace to shed 25% this year, a worse drop than the S&P 500 index’s

SPX,

roughly 17% slide, according to FactSet.

“The bigger issue, I think, is going to be how do the borrowers refinance,” said Alan Todd, head of CMBS research at BofA Global. “And that’s not just on office. It’s if you’re in a property where now valuations are lower, your rate is significantly higher, how are you going to refinance successfully?”

What if prices tumble 30%

Commercial property prices cooled slightly in recent months, but still were up 7.3% on the year through October, according to the RCA CPPI index. What’s more, prices were an eye-watering 123.5% higher from 10 years ago.

Todd at BofA Global thinks property prices could drop 20%-30%, then see an uneven recovery. “You’re talking about a secular, not cyclical, change for certain property types, whether those are regional malls or some of the lower quality offices,” he said. “Some of those could be fairly problematic.”

Even so, Todd doesn’t foresee a deluge of foreclosures, distress or the magnitude of losses that followed the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, since many lenders now have more leeway to work with borrowers to wait out the storm.

Borrowers might also tap into equity taken out of properties to fund tenant improvements or to get a new loan. “We’ve had 10 years of cash-out refis, so you gotta believe they have money they can cash in,” Todd said.

Analysts at Morgan Stanley estimate that some $300 billion in “dry powder” also sits on the sidelines, which potentially could be deployed and limit the slide in property prices.

Although, with sales volumes largely stuck in a rut, any buyer trying to estimate where property values might ultimately shake out is taking a stab in the dark. The Fed also expects to keep borrowing costs up, until inflation finds a clear path down.

“There is an estimated $450 billion of loans that comes due in each of the next four years,” said Rich Hill, head of real estate strategy and research at Cohen & Steers, a real assets-focused investment manager. “The market is having to come to the reality that the days of cheap money are gone.”

Still, Hill sees commercial real estate heading into 2023 on relatively solid footing, given prudence from lenders in the past decade and his firm’s forecast for net-income and earnings growth to remain higher if the U.S. economy sinks into a recession.

“It’s likely that property values fall in the next 12 to 24 months,” he said. “But in an environment when cash flows are good, I don’t think lenders will sell distressed properties into a challenging market.”