As the drought persists, one enchanted garden at the foot of the Sierra tends to people

“A fallow field is a sin.”

— John Steinbeck

At the foot of the Sierra, where square acre after square acre of industrial farmland is planted in precise rows, an unusual garden grows and climbs and spirals.

Three types of guavas, papaya, bananas, jujube — fruits that speak of faraway homelands — flourish at the 13-acre Woodlake Botanical Garden, which is wedged between a road and reservoir on a skinny, left-over piece of land where railroad tracks once ran. No chemicals are used here. Visitors are welcome to pick any fruit they see and to sit in spots so deeply shaded they stay cool in the summer heat and dry in the rains that don’t come often enough.

Each inch of irrigation water is counted and will soon have to be defended. But founders Olga and Manuel Jimenez argue that even in a state with an intensifying drought and conflicting needs, what’s here is a priority: a charmed space tended by a volunteer workforce of Woodlake children and teenagers stretching back 30 years. As a reminder of the garden’s true purpose, Manuel has lined the trails with plaques bearing quotes.

“If you want one year of prosperity, grow grain. If you want 10 years of prosperity, grow trees. If you want 100 years of prosperity, grow people.”

— Chinese proverb

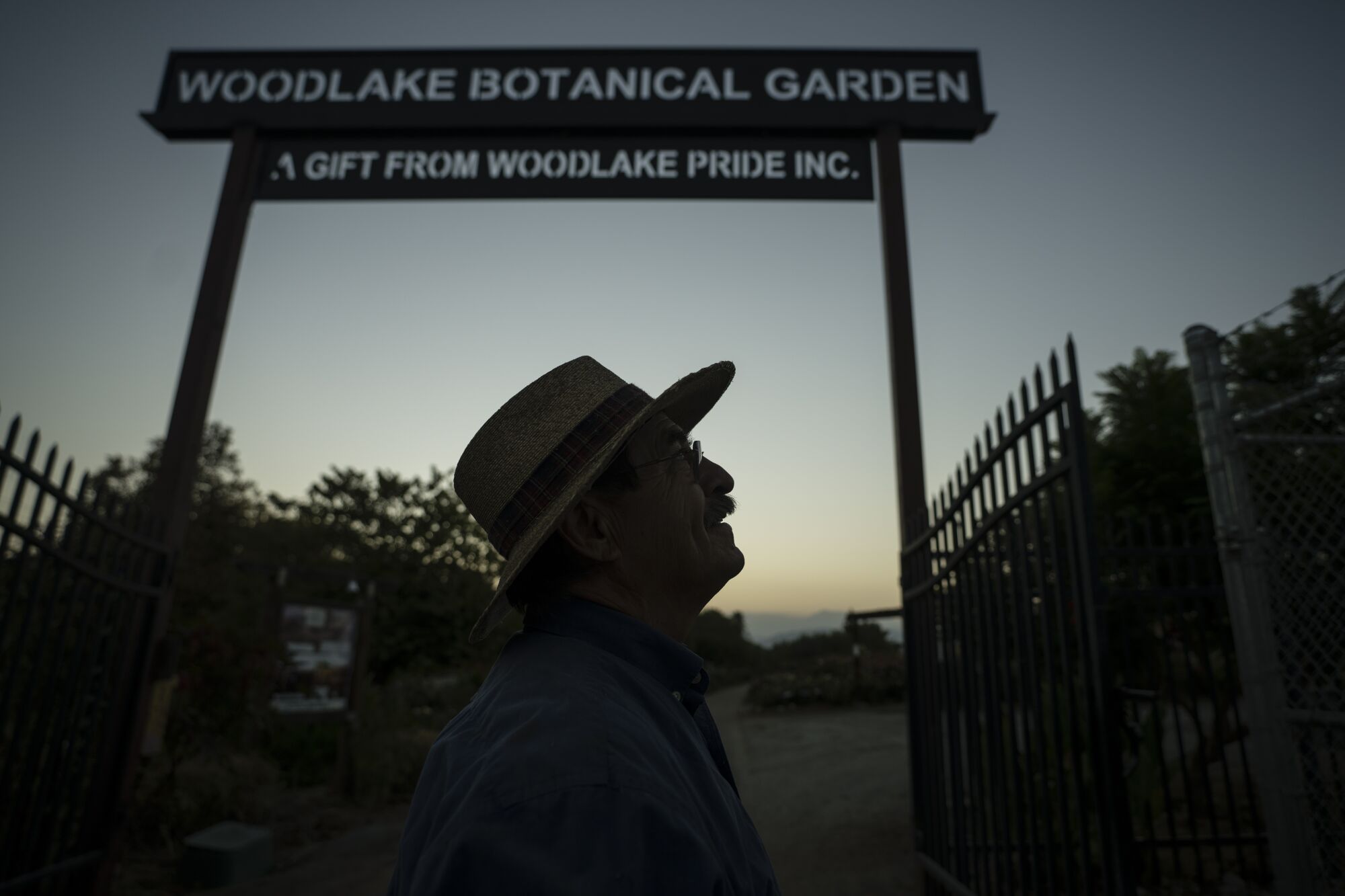

Manuel Jimenez watches a Canada goose passing over as he opens the gate at the Woodlake Botanical Garden.

(Tomas Ovalle / For The Times)

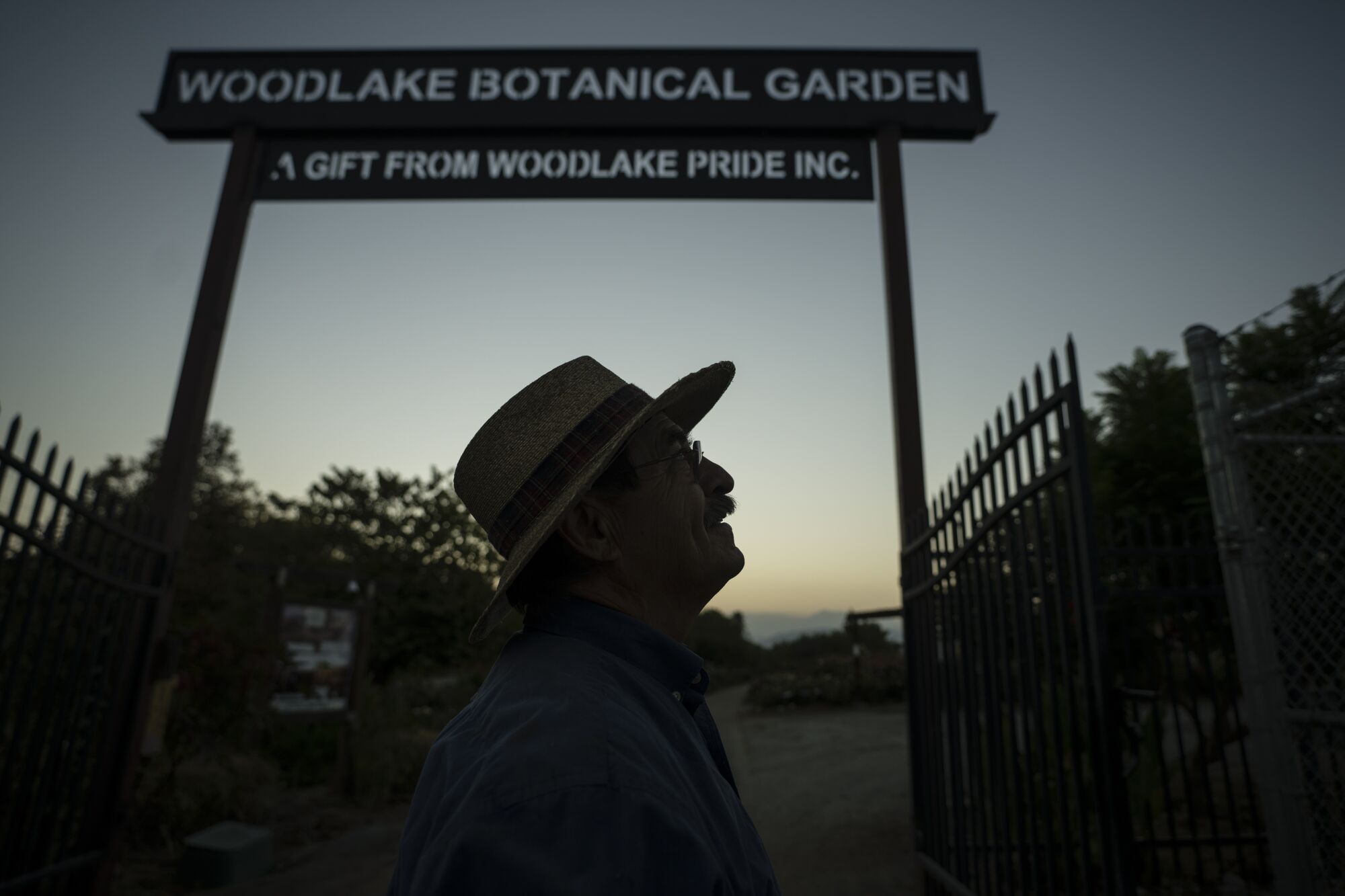

The Woodlake Botanical Garden.

(Tomas Ovalle / For The Times)

On a recent Saturday Hamida Mohamed, 17, and Alexandra Martinez, 16, worked in the garden. They’ve been inseparable since the day Alexandra introduced herself to the new girl at school because she figured being new is scary.

Hamida, who arrived this year from Yemen, wore a rose-colored hijab. She speaks Arabic, Spanish and Chinese but is still learning English. Her father owns Woodlake Drive-In, a popular burger stand where the Jimenezes often buy lunch for their volunteers.

Olga showed the girls how to deadhead roses and immediately delved into their lives.

“Tell me, mija, is your dad going to let you go to college? Is he going to let you date?” she asked Hamida. “Many of the Mexican girls can tell you that I talked to their father about the need for women to be independent, and I know your dad.”

Hamida smiled and said, “I will go to university.”

She used a translation app on her phone to type out her plans: “My dream is to be a filmmaker, writer, film director and cinematographer.”

In the meantime, Manuel loaded a group of boys in an old pickup and drove them a mile down the garden, past apple and citrus trees, to a spot that was wild and overgrown. He directed Alonso Velasquez, 17, to hand out weed whackers and show the other boys how to use them.

“I could tell Alonso was a leader right away,” Manuel said. “Because when a job was done, he’d say, ‘What next?’” There are not many agricultural skills that Alonso — who runs track, keeps his grades high and, later on this day, will be an escort at a quinceañera — doesn’t possess.

Manuel Jimenez directs volunteer Alonso Velasquez, 17, at the Woodlake Botanical Garden.

(Tomas Ovalle / For The Times)

Kevin Perez, 15, Rodrigo Cruz Perez, 17, Gilberto Gonzalez, 15, and Uriel Rios, 15, share a laugh at the Woodlake Botanical Garden.

(Tomas Ovalle / For The Times)

He grew up working summers on his family’s avocado ranch in the Mexican state of Michoacán. Two years ago, he said, he was kidnapped by a cartel member who hid him in a forest for three days. But a more powerful cartel stepped in and helped his family find him after they paid a ransom.

“The different cartels are almost like how Manuel handles pest control in the garden,” Alonso said.

Everything growing here attracts every pest known to it, but the garden also draws the natural predators of every pest, to strike a balance.

Manuel studied agricultural plant science at Fresno State and spent 30 years as a University of California small farm adviser before retiring nine years ago. He spearheaded efforts to grow exotic, niche crops in the San Joaquin Valley and was key in founding the region’s blueberry industry.

But his and Olga’s biggest gifts may be their talents as storytellers.

Manuel and Olga Jimenez at the Woodlake Botanical Garden.

(Tomas Ovalle / For The Times)

“The whole time you’re with them, they tell stories. There’s funny ones and dumb stories. And then there’s the ones that are really important things for you to remember,” said Karem Barreto, 18, who had recently added violet highlights to her dark hair.

“Hey, did you notice Karem has developed a phosphorous deficiency?” Manuel teased her, a reference to the shortage that turns the leaves of some plants purple.

Barreto’s family moved from Los Angeles to Woodlake when she was in the seventh grade.

“We were suddenly in the country,” she recalled. She remembers being almost scared of the wide, open spaces.

“My parents are very protective, and they weren’t sure about me and my sisters going to the garden. But then they met Manuel and Olga and said, ‘Oh, as long as you’re with them, you’re good.’” She now balances volunteering at the garden with studying at College of the Sequoias, a community college in Visalia. She plans to be a special needs teacher.

::

Olga Jimenez speaks about the volunteers at the Woodlake Botanical Garden.

(Tomas Ovalle / For The Times)

Manuel and Olga grew up in this Tulare County town of 7,708 back when it was about half that size. The screen saver on Manuel’s phone is a photo of them as high school sweethearts in 1968.

They were from farmworker families, and kids from those families were often directed to a nonacademic track.

Olga, a gifted student, was determined that wouldn’t happen to her.

One year, she and her family returned from following the crops after school had started. Unbeknownst to her, Olga had been shifted to an English class that was known to be for “slow” students.

She went to the advanced class she had registered for. The administrators told her there wasn’t room. She said she would sit on the floor. They told her they couldn’t have her sitting on the floor.

She said, “Then you’ll have to bring me a desk,” and they did. Olga went on to attend Fresno State.

A flock of pelicans resides at Bravo Lake, adjacent to the Woodlake Botanical Garden.

(Tomas Ovalle / For The Times)

A spider sits in his web at the Woodlake Botanical Garden.

(Tomas Ovalle / For The Times)

Barreto, listening to Olga’s story, nodded. “See?” she said. “That’s about determination. It’s one of the ones to remember.”

From the time he was a teenager, Manuel has almost always had a camera around his neck, and the garden is sprinkled with photos of volunteers through the years.

Manuel pointed to one showing a chubby-cheeked preteen. He said that the boy had good parents and showed leadership, but that a gang recruited him in middle school.

“He shot two people,” Manuel said, staring at the photograph. “Two people lost their lives, and he’s spending the rest of his in prison. We didn’t save them all.”

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

— Margaret Mead

The Woodlake Botanical Garden grew out of another clash with authority. In the early 1970s, newly married and determined to improve the bad side of town, the Jimenezes led children and teens in beautifying projects. The wall of a former bar was covered in gang signs and profanity, and the owner agreed to let them cover it with a mural.

Olga and Manuel gave each teen a section of the wall to paint.

Manuel Jimenez takes a call at the Woodlake Botanical Garden.

(Tomas Ovalle / For The Times)

It was the era of the Delano grape strike, which rattled the power structure of the region. One teen painted “raices” (“people”) and a raised fist. Another added the United Farm Workers symbol.

The all-white City Council sent police to serve a cease-and-desist order and said it would paint over the almost-finished mural.

Manuel went to California Rural Legal Assistance for help.

It was a hot issue, and community members packed the City Council meeting that week. Old friends, even Mexican families, were mad at Olga and Manuel. “Why are you causing division in our town?” a close friend asked them.

The City Council declared the mural violated a sign ordinance and then announced the meeting was over. Then the CRLA attorney stood.

“I know you called this meeting to an end, but you should reopen it or tomorrow there will be a federal lawsuit filed over free speech,” Manuel recalled him saying. The council went into a closed-door meeting. The mayor stomped out, announced the mural would stay, banged the gavel and left.

Eventually, the Jimenezes and the city were able to negotiate a friendlier alliance. In 1999 when Woodlake obtained a barren strip of land through a federal grant, the couple agreed to turn it into a permanent garden with their brigade of youthful volunteers they’d christened Woodlake Pride. The city would provide water and insurance.

Seed money for equipment and plans came from Everett Krackov, the owner of a local olive processing plant. As a teenager, Manuel had worked at the plant, but he quit after Krackov yelled at him for being slow.

Bravo Lake is adjacent to the Woodlake Botanical Garden.

(Tomas Ovalle / For The Times)

Years later, Krackov pulled up to an early Woodlake Pride project and asked Manuel whether he fed the kids who were volunteering. Manuel said that sometimes community members baked cookies.

Column One

A showcase for compelling storytelling from the Los Angeles Times.

Krackov gave Manuel a $500 check for lunch money. The account opened with that money is still the one that pays for after-work trips to the drive-in — an account held by Woodlake Pride, now an official nonprofit organization.

Around the time they received the land, Bank of America closed its Woodlake branch. Krackov, who had a talent for raking people over the coals, called the regional office and told officials that they had abandoned a community and that the least they could do was support this project. Woodlake Pride received a $10,000 donation from the bank.

Sooner or later, most people in town spend time in the garden. On this day, a young couple sat beneath an apple tree stealing looks at each other between looking at their laps. Two cousins walked two dogs. A visitor from Orange County shouted her thanks and put money in a donation box as she was leaving.

“That doesn’t happen very often,” Barreto said. “It’s like the donation box grows invisible when people look at it.”

For decades, the Jimenezes asked for the garden to be included in the city budget, but they were always turned down. At one point they walked away: Let the city see what it took to run the place. They returned to their positions when they couldn’t bear to see more plants die. Two years ago, the city started budgeting $25,000 per year, funded by California’s marijuana business tax.

“The true meaning of life is to plant trees under whose shade you do not expect to sit.”

— Nelson Henderson

At 72, Olga and Manuel have moved from outside agitators to community members of standing.

They are even depicted on a city-sponsored mural in the center of town.

“I didn’t want it,” Manuel said. “It makes it seem like we are no longer fighting for the people. We’re still fighting.”

During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, many workers in Tulare County died. The jobs in the rural areas are in packinghouses and food processing plants. People went to work whether they were sick or not.

“The businesses didn’t want anyone to know that they were rampant with COVID. They were trying to keep it hush-hush,” Manuel said.

Starting in April 2020, every Saturday evening Manuel and Olga lighted luminarias in the garden for every death in Tulare County. They did it for more than a year, and by 2021 there were 841 candles. The garden was closed, but people could see the glow from the street. Manuel posted photos of the growing number of candles on their Facebook page. In the comments, people told the stories of those who died.

One of the boys working on this Saturday lost his mother. Manuel and Olga’s close friend died, and then, one by one, most of their friend’s extended family.

“It’s very important to remember this time,” Olga said.

The last three years have not only been defined by a global pandemic, but they’ve also been the driest in California’s recorded history. Recently, Olga and Manuel went for a drive to see what was going on in the fields beyond Woodlake. They saw thousands of acres of newly planted orange trees.

“We are in a serious crisis. It might already be too late,” Manuel said. “The simple truth is that there isn’t enough water. Choices have to be made.”

They’ve been warned that city water to the garden could be cut back as the drought continues. “But it’s the community places — the shared spaces of beauty and food — that we must keep,” Olga said.

It was the end of the workday, and she rested, legs outstretched and tools beside her. “When the good Lord calls me, I’m going to tell him, ‘Just a minute while I get my clippers,’” she said. Then she moved to the shade of a Pakistan mulberry tree — her favorite spot, one where people tend to gather.

She said that what is learned in the garden — how to work with others, how to grow food, the importance of resting in the shade and, most of all, sharing stories — are the tools of survival.

“These young people need to know that they’re not alone in the fight ahead,” Olga said. They carry the courage, love, humor; the losses and injustices weathered before them.

“No matter what, this garden stays,” Olga said. “It’s vital.”